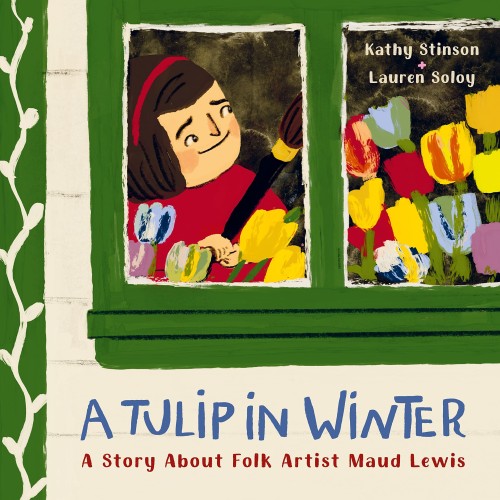

Getting to Know Maud Lewis

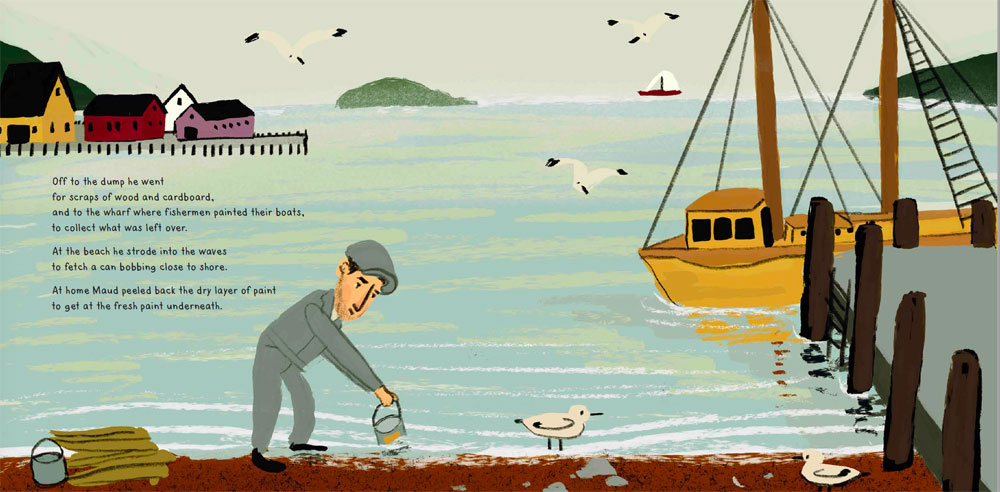

In contrast to the often bleak landscape and harsh climate of rural Nova Scotia that formed the backdrop of her life, Maud’s paintings brim with vivid, joyous colour. Was she escaping the miseries of her life through her painting? Or was she simply adept at seeing the beauty in the world and expressing it through her work?

When Maud was in grade five, she was fourteen years old. Was this because of her illness? because she was bullied? or because early in the twentieth century there wasn’t always a teacher available where she lived?

When Maud’s daughter, Catherine Dowley, showed up on her doorstep in 1950 (unlike what happens in the movie “Maudie”), Maud told Catherine she couldn’t be her daughter because she’d given birth to a baby boy who, very soon after, died. Was that because that’s what she’d been told by her parents and she believed it? Because she didn’t want Everett to know about the baby she’d had years before they married? Or because she wanted to keep that painful part of her past behind her?

Despite all my research, I couldn’t come up with definitive answers to any of these questions. There may well be truth in all the possibilities. During the writing of A Tulip In Winter, if I didn’t know the answers, I opted simply to avoid the questions.

As I wrote in a guest blog post last month, I left out the mention of Maud’s baby altogether. I didn’t mention Maud’s poor attendance and performance at school either, although I suppose I could have. It’s not as complicated a matter as trying to put the shame of having a baby out of wedlock into context for today’s young readers — who I think will arrive at their own interpretation of the contrast between Maud’s joyfully exuberant art and her circumstances. (I may have steered them a little in the book’s back matter.)

One aspect of Maud’s life I found lots of material about related to the kind of man Maud’s husband was. There is plenty of evidence in interviews and film footage that suggests Everett likely wasn’t an easy man to live with. But several things convinced me he deserved more credit than many were willing to give him.

He often appeared in Maud’s paintings as a strong and hard-working man. When Maud became ill, Everett, who did not like to spend money, tried to pay the ambulance driver what would have been for him a lot of money, in an attempt to convince the driver to take Maud to the hospital in Halifax, where he thought she’d get better treatment than she would in Digby. Maud said near the end of her life, “I was loved.” And I believe Maud loved Everett too.

And so, when I introduced him into the story, I wrote:

Everett Lewis was as gruff as a billy goat.

I also said:

Everett was strong in body. Maud was strong in spirit. They got along the way certain colours do.

And here’s Everett’s last appearance in the story:

After a time, Maud was in too much pain to walk or even to paint.

Everett carried Maud to his wheelbarrow.

He pushed it to where she could see the sweet peas blooming.

“Thank you, Ev,” she said.“

In case I’d downplayed Everett’s “gruff as a billy goat” aspects more than I should have, I included a few words about him in the back matter (which focuses mostly on the “one-of-a-kind” artist and her “one-of-a-kind” house):

Was Everett miserly and cruel, as some people believe, because he never spent money even when he had it, on things that would have made the house more comfortable for Maud? Things like electricity, a screen door, and indoor plumbing? Or was Everett simply content with how things were, or afraid of spending money because of his poor background? Whatever the case, Everett did make it possible for Maud to pursue her passion for painting, and she relieved him of a deep loneliness.

What biography have you read or written that left you wishing you could know more about its subject?

Share this post:

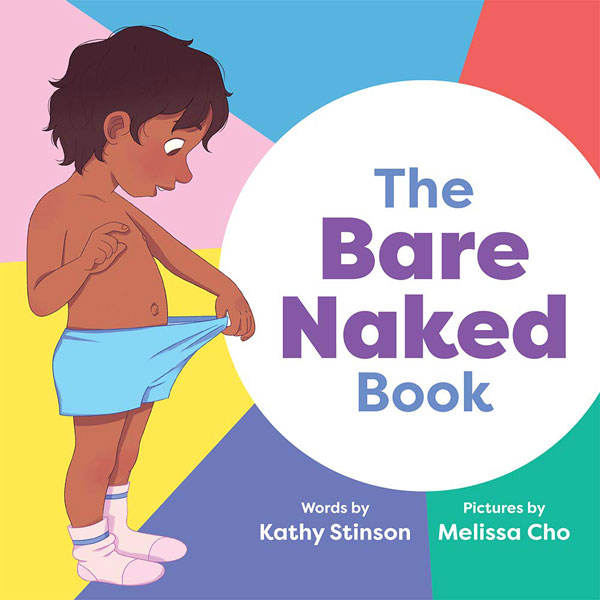

Kathy Stinson is the author of the classic Red Is Best, the award-winning The Man with the Violin, and the GG shortlisted The Rock and the Butterfly. Her wide range of titles includes picture books, fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. She has enjoyed the privilege of meeting with her readers in every province and territory of Canada, in the United States, Britain, Liberia, and Korea. Currently president of CANSCAIP (the Canadian Society of Authors, Illustrators, and Performers), Kathy lives in a small town in southern Ontario.

This is a wonderful glimpse into the kinds of things that make up the layers of consideration an author experiences as a story is written. Thank you for sharing what you went through in choosing what to include and what to set aside as you wrote this wonderful story.

Thank you, Peter. I’m glad you enjoyed the post — and the story!

I cannot wait to hold your new book in my hands and thanks for writing such a meaningful story. But then, you always do!

Interesting you would say you can’t wait to hold this book in your hands, Wendy, because A Tulip in Winter is definitely one of those books that’s a sheer pleasure to hold, thanks in part to the quality of its paper and the care Greystone took in its design and production. And Maud’s story is great and Lauren’s illustrations are too. Thank you for your kind words. 🙂

will I be able to order this book in Ireland?

regards

Maria Stenson.

Hi Maria. Thanks for your interest in A Tulip in Winter. I think an independent bookseller in Ireland should be able to order the book for you. Its ISBN number is 978-1-77164-951-3. Failing that, you can probably get it through Amazon. (Never my first choice personally, but in a pinch…) I hope you’re successful, one way or another. I love to think of this book I’m so pleased with (am I allowed to say that?) making its way into Ireland. 🙂

Best,

Kathy