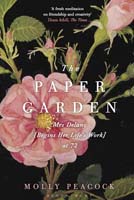

Review of The Paper Garden by Molly Peacock

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72 by Molly Peacock is a beautiful book.

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72 by Molly Peacock is a beautiful book.

Of course it’s beautifully written. The story of this 18th century botanical collage artist is by poet Molly Peacock, who draws fascinating parallels, along the way, between her own life and that of Mary Granville Pendarves Delany.

Designed by Scott Richardson, the book is itself an art object. Just hold it in your hands, flip through its heavy pages to the full-page colour plates and smaller close-ups of floral details, and notice the scissors motif that is part of its design, and you’ll begin to see why I say this.

I’m not a visual artist (although I have, from time to time, enjoyed putting pencil, pastel, or paint to paper), but I loved how Molly Peacock described the work that Mary Delany did in the later years of her life. The story of her life and work is inspiring, and what the book says about various aspects of creativity felt relevant to me, as a writer. Here are a few passages I bookmarked as I read the book, knowing I would want to revisit them. (I’m providing page references, but I urge you to read the whole book so you can encounter these excerpts again in their proper context.)

On perfectionism (p28):

Great technique means that you have to abandon perfectionism. Perfectionism either stops you cold or slows you down too much. Yet, paradoxically, it’s proficiency that allows a person to make any art at all; you must have technical skill to accomplish anything, but you also must have passion, which, in an odd way, is technique forgotten. The joy of technique is the bulging bag of tricks it gives you to solve your dilemmas. Craft gives you the tools for reparation. And teachers give you craft, for a good teacher urges you beyond your childish perfectionism. From there you proceed into the practice that eventually becomes expertise.

On observing (p101):

Robert Phelps, a biographer of Colette, said about watching, “Along with love and work, this is the third great salvation. For whenever someone is seriously watching, a form of lost innocence is restored. It will not last, but during those minutes his self-consciousness is relieved.”

Noticing keeps you alive. When we say, “I felt so alive!” doesn’t it mean we were observing the ordinary world around us as if it were new?

On describing (p102-3):

Foolishly, for most of my life I separated looking and organizing from creativity. Poetry, I thought when I was young, sprang solely from the emotions, and emotions certainly had nothing to do with the orderliness of science. Yet the first thing I did when I was overwhelmed by the vastness of a subject or a feeling was to start observing so that I could describe it to myself. You might not be able to draw a conclusion from what overwhelms you, but if you describe it, you will come to know it. And when you come to know it, you are less afraid of it. And when you are no longer afraid, you have balance. And when you have balance, you have the poise that is control. The systematic noticing of details is at the foundation of science, too. Mrs. Delany did not live in our ultra-specialized world, but she was poised at the beginning of it. She loved differentiating all types of details; in describing as she did, she participated in the birth of taxonomy. The lines between science and art in her day were fluid, but in 1966 they had become as thick as the stays in eighteenth-century ladies’ clothes.

Mrs. D enjoyed taking in vast quantities of particulars. After she collected her shells, she tucked them into special cabinets. She scrutinized them and mentally noted minutiae. Thou she hardly could have known it, she was preparing herself for her later work, busy noting the natural world just as carefully as if she’d had to record data for a biology class. Such observing is discipline, practice, a way of being that leads to art.

On craft (p288):

Craft is engaging. It results in a product. The mind works in a state of meditation in craft, almost the way we half-meditate in heavy physical exercise. There is a marvelously obsessive nature to craft that allows a person to dive down through the ocean of everyday life to a seafloor of meditative making. It is an antidote to what ails you. … One can lose oneself… and the loss of the self within safe confines nurtures the imagination.

On observing, again (347-8):

Observation of one thing leads to unobserved revelation of another. That’s how I don’t know exactly when I crossed the line to lose my fear. I was walking along in life like the amateur conchologists I have watched for years on the beaches of Sanibel Island, Florida. They never see the sunsets. They are always looking down to grab their finds, their shells. While I was examining the mosaicks [Mrs. Delany’s botanical collages], looking down at my finds, above me another part of my life was standing, unknown to me, looking at what I’m not sure, perhaps a metaphorical sunset. This other part was transforming even as I looked as hard and as closely as I could at papery things all tiny and nearly incomprehensible. Direct examination leads to indirect epiphany. Examine this world, Arikha and Moore say to us in their more elegant ways, as does Mrs. D. in hers: even if that is only the gristle in the drain trap of a sink, or the pearly glue at the tip of a pistil.

Whatever this holiday season may mean for your life in the coming days, I hope you’ll find some peace in observing, perhaps describing, maybe even engaging in craft. And if you’re still doing holiday gift shopping, you might consider whether someone on your list might like to receive their own copy of this “Globe and Mail Best Book” that is part biography, part memoir, and part meditation on creativity: The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany Begins Her Life’s Work at 72.

Share this post:

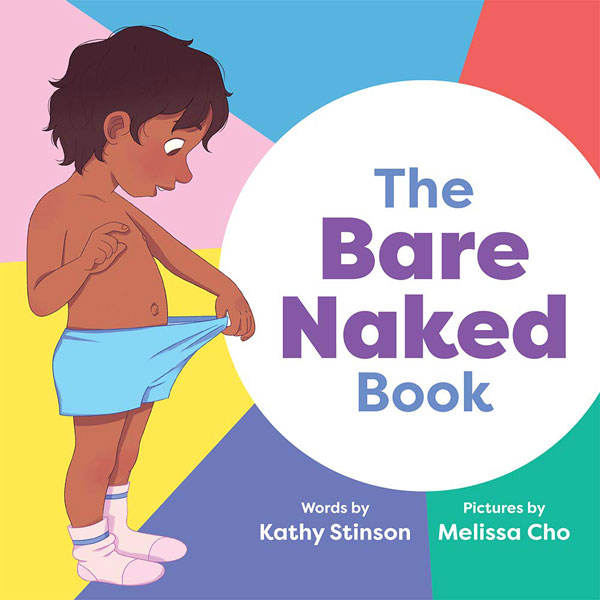

Kathy Stinson is the author of the classic Red Is Best, the award-winning The Man with the Violin, and the GG shortlisted The Rock and the Butterfly. Her wide range of titles includes picture books, fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. She has enjoyed the privilege of meeting with her readers in every province and territory of Canada, in the United States, Britain, Liberia, and Korea. Currently president of CANSCAIP (the Canadian Society of Authors, Illustrators, and Performers), Kathy lives in a small town in southern Ontario.

This sounds like a very inspiring read for people of any age who think it's too late for them to start something new and achieve any level of proficiency. Do you think it would be a good one for a book group?

I hadn't thought of it as a Book Group book, Janet, maybe because my group tends to read fiction, but there are certainly lots of angles from which a group could come at a discussion of it.

If your group decides to do it, it might be fun to have scissors and fine paper on hand for everyone there.

I'm intrigued… I'll let you know if it happens, but I think we've chosen our books for the next few months, so it won't be for a while!

That's good, Janet, because I just loaned my copy of The Paper Garden to someone last night. Peggy. I'll be happy to lend it to you next so you can check it out.

Great – thank you!